We have all heard the adage: “Where there’s a will, there’s a way.” When it comes to making a sweeping shift from carbon-emitting transportation fleets to clean-breathing zero-emission vehicles, the will most certainly is strong. In the U.S. alone, 15 states and the District of Columbia have signed a Memorandum of Understanding to make strides toward the use of zero-emission medium- and heavy-duty vehicles, including city bus fleets. It comes as no surprise that California is leading the charge (pun intended). The collective will is growing and encouraging for the future state of air quality and the long-term health of our planet.

But what about the way? Therein lies the challenge. We most certainly don’t want the road ahead, paved by good intentions, to end up you know where: an overheated planet that eventually self-combusts.

Dramatic, yes. But we must figure out how to answer this critical question in a realistic way considering that transportation contributes to 29% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions annually. How can heavy-duty fleet owners, including local governments who have their eye on EV options for public transportation as well as commercial companies with the same mindset, marry the will and the way to pave a better road ahead?

Rolling out a shiny, new fleet of ZEV buses is only the first step — albeit an impressive one given the hurdles of extra cost, procurement challenges, and acquiring capacity for charging activities. But building out the right electrification infrastructure to support the ZEV fleet is where well-intentioned organizations face the biggest roadblocks. What good is the ZEV fleet if grid capacity or alternative fuel supply cannot support it? Or if that grid capacity or hydrogen is supplied by fossil-fuel based power generation facilities?

Think about a related scenario in many of our work-from-home, daily lives. What typically happens when everyone in your household is online at the same time — whether yawning through a late virtual meeting, doing homework, binge-watching “Stranger Things,” etc. Buffering. That maddening, inevitable buffering when the internet infrastructure cannot support the familial demand for connectivity.

The same is true of powering EV fleets with the electric grid. The underlying infrastructure to support widespread, capital cost-friendly, reliable, and resilient electrification simply isn’t up to speed. Despite the groundswell of excitement and support for shifting to electric vehicles in the transportation sector, the electrification of heavy-duty transportation requires much more than swapping out a diesel truck for a battery-electric one, or a hydrogen one for that matter. There is a clear change in fundamentals at play — that is, route planning constraints, emissions regulations, electricity vs. fuel management, idling and pre-conditioning, maintenance cycles, vehicle off-line duration for charging, and other operational KPIs.

The grid as an obstacle to widespread implementation of EV fleets

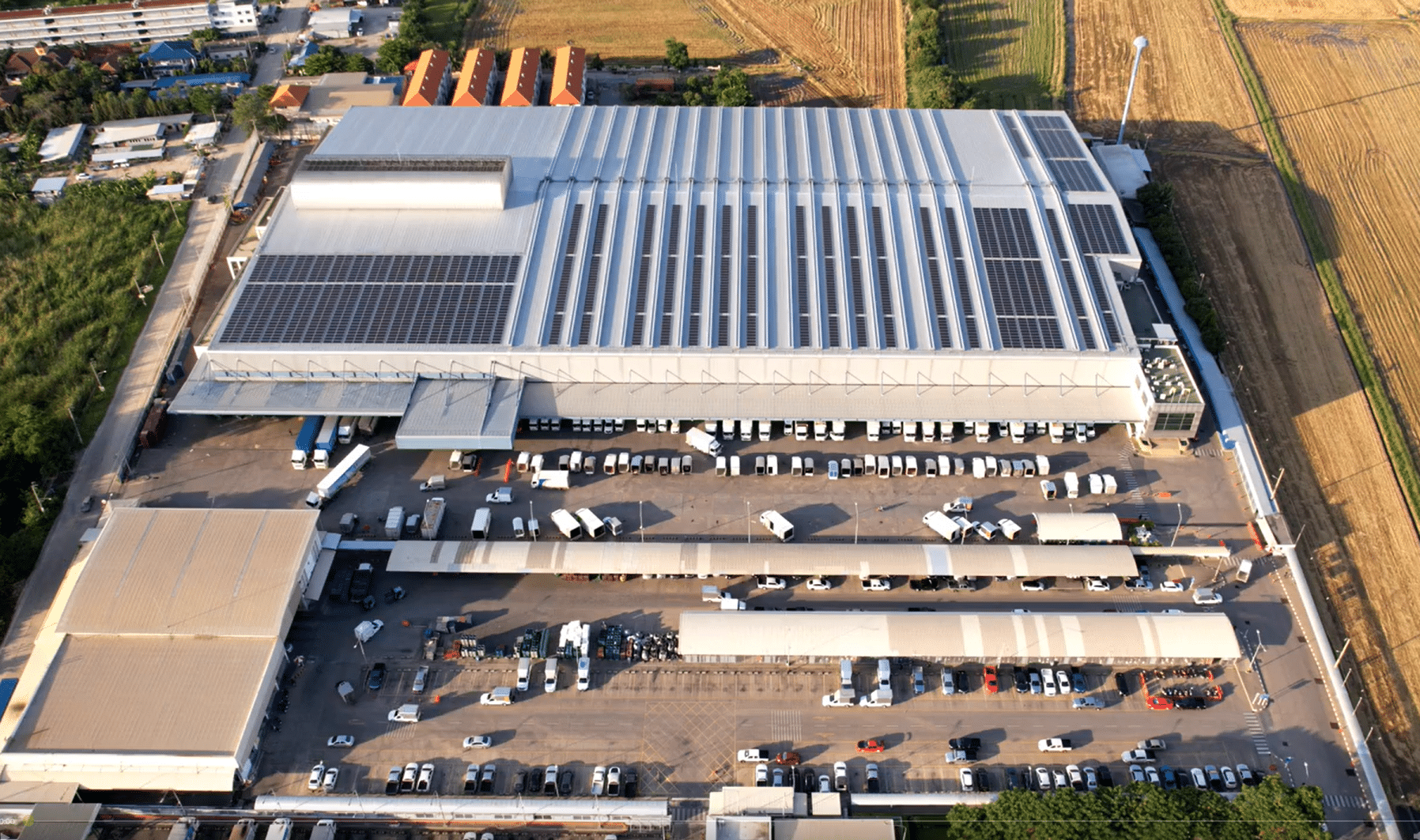

Quite frankly, the grid itself, and how we think of it and meeting our power demands, may be the biggest barrier to EV deployment. The electrification of transportation understandably challenges the local utility, especially for heavy-duty vehicles, due to the large electric need at locations where power wasn’t previously needed – think about parking lots with lighting now needing as much power as a hospital or factory. Grid support of a bus depot or last-mile delivery distribution warehouse for heavy-duty EVs can take years in planning and execution of the grid upgrades needed to deliver capacity. Unfortunately, that cost and time delay is one that the customer must bear during the energy transition.

So how can we make a measurable change — now? One answer: onsite energy and microgrids.

A cost-friendly model for deployment

A microgrid at a regional distribution center offers the ability to substantially reduce the carbon footprint while also increase the ability of that site to be a flexible resource for the grid. The distribution center is more energy flexible (thanks to the microgrid’s high level of automation and digitalization), and this means that it can balance the EV charging behind the meter with grid services in front of the meter. Given that the ETC projects a 250% growth in heavy-duty transport volumes by 2050, having the load-side flexibility to scale up ways to meet this grid demand is imperative.

A flexible solution to manage local electricity demand

A microgrid at a heavy-duty EV distribution center offers the ability to substantially reduce the carbon footprint while also increasing the ability of that site to be a flexible resource for the grid. The distribution center is more energy flexible (thanks to the microgrid’s high level of automation and digitalization), and this means that it can balance the EV charging behind the meter with grid services in front of the meter. Given that the ETC projects a 250% growth in heavy-duty transport volumes by 2050, having the load-side flexibility to scale up ways to meet this grid demand is imperative.

Advantages for long-term operations and maintenance (O&M)

It’s clear that electrification of transportation, for most segments, provides a long-term O&M advantage. The number of moving parts in an electric bus or truck when compared to a diesel or gas one is reduced from 3,000 to 30, resulting in far less maintenance. The combination of no oil changes, fewer lubricants, and no on-site fuel storage tanks also results in less environmental compliance reporting or fines for spills and clean up.

Use case: Get on the electric bus!

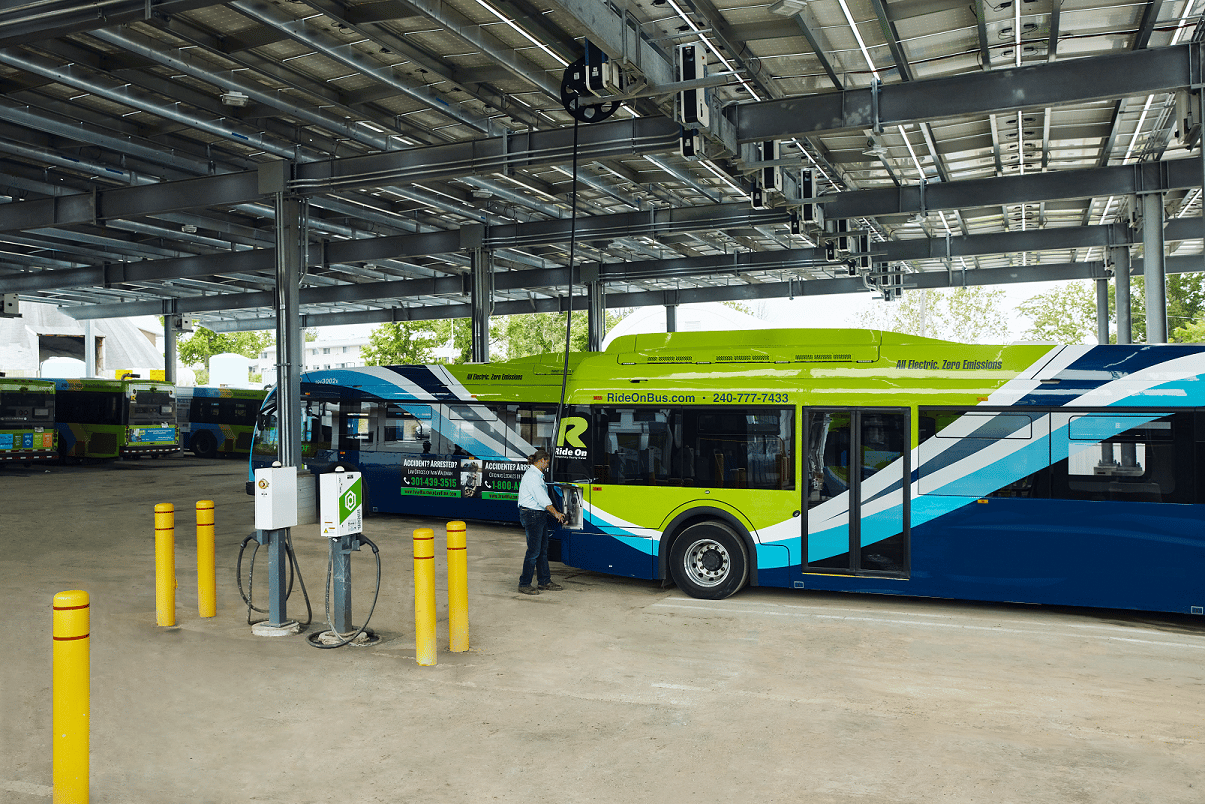

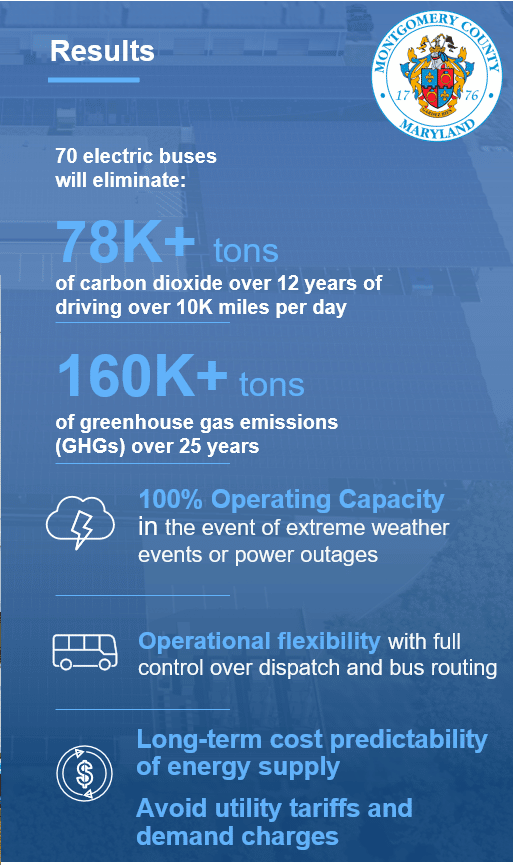

Montgomery County, Maryland, has contracted with AlphaStruxure to deploy a microgrid that can handle the transition of 70 diesel buses to electric ones. This effort is part of the county’s goal to reach net-zero emissions by 2035. Maximizing onsite renewable energy—via a microgrid for its Brookville smart energy bus depot—is the country’s chosen road to decarbonization. This route allows Montgomery County to avoid utility tariffs and demand charges. The results — 62% reduction in day 1 carbon emissions — are eye-opening (and attainable) for all.

Why not just stick with the grid for electrifying vehicles?

Utilities have a lot on their plate with operations and maintenance of aging electric grid infrastructure as well as interconnecting much needed renewable generation. In addition, utilities are in the middle of a multi-decade improvement in their networks to utilize smart grid and advanced metering infrastructure. This, too, is ever growing as grids age and renewables increase.

Electrification of passenger and light-duty EV is broad and ubiquitous across the electric network which is best served by electric distribution grids; however, Zero Emission Vehicle fleet conversions in dense, specific sites like bus depots and last-mile delivery centers are best served by smart, on-site distributed energy resources — microgrids. This approach greatly reduces the burden on the local grid to upgrade distribution systems for individual customers or spread that burden to all rate payers who may be required to subsidize these investments.

We’re on the right road.

I personally am encouraged that the road ahead for electric heavy-duty surface transportation is not far off. ETC sums up “the way” quite nicely: “The path to decarbonization in heavy-duty road transport is relatively clear: electric vehicles will deliver huge increases in efficiency compared to internal combustion engines and will likely become the dominant technology.”

Let’s make sure the infrastructure is in place ahead of time to support this vision — moving us all that much closer to meeting the global MoU launched at COP26 to “accelerate the zero emission medium- and heavy-duty vehicles market by setting a 100% zero-emission target including new bus sales by 2040.”

Montgomery County, Maryland, is leading the charge with electric buses and the Brookville Smart Energy Bus Depot. Who else is ready to jump on board?